New study reveals pre-colonial maize agriculture and animal management in the Bolivian Amazon

Biochemical analysis of the bones of humans and muscovy ducks reveals the significance of maize to diets at the same time as significant socioeconomic complexity.

Over the past two decades, there have been dramatic changes in our understandings of human history in the Amazon. Instead of perceptions that it could only host small groups of hunter gatherers, multidisciplinary research has revealed a variety of evidence for plant cultivation and domestication and the emergence of vast urban networks which may have sustained up to 20 million people at the time of European invasion.

While evidence for experiments with plant cultivation extends back as far as 10,000 years ago in the Amazon Basin, the contribution of different domesticates to diets across this vast region - an area larger than Europe - remain poorly understood as a result of challenging preservation conditions in tropical environments. This is particularly problematic given debates relating to whether the arrival of maize in the region around 3,000 BCE resulted in major socioeconomic changes.

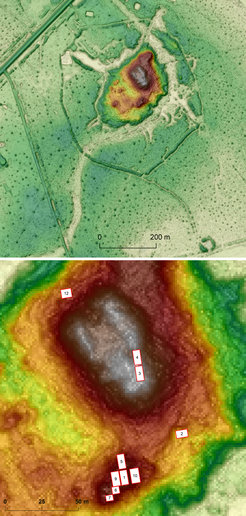

In a new study, members of the isoTROPIC Research Group together with collaborators in Brazil, Germany, and the United Kingdom, investigated this question. They applied stable isotope analysis to human remains from the monumental mound sites of Salvatierra and Mendoza in the Bolivian Amazon (Llanos de Mojos), dating from approximately 700 to 1400 CE. These sites are part of the Casarabe culture, which exemplifies one of the largest and most intricate forms of ancient low-density urbanism in the Amazon and South American Lowlands.

The researchers’ findings indicate that maize was the primary staple of the Casarabe people for at least 700 years, despite a slight decline in its consumption over time. This suggests that sustainable and reliable maize agricultural practices were a feasible subsistence strategy in ancient Amazonia.

Additionally, the application of this same methodology to animal remains shows a significant maize diet among muscovy ducks (Cairina moschata), occasionally surpassing that of humans, implying that these ducks were intentionally fed. This evidence of animal management has not been documented before in the archaeological history of the South American lowlands.

Overall, the team’s data adds to the emerging complexity and diversity of socioeconomic, ecological, and subsistence strategies that sustained large Indigenous societies across the Amazon Basin during the Late Holocene. Future work exploring this diversity promises to further enrich our understanding as to how these communities interacted with the forests of the region, combining varied land use activities with the maintenance of significant portions of tropical forest.